|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||||||||||

The history of a sculpture by the sculptor, Roger Arvid Anderson |

||||||||||

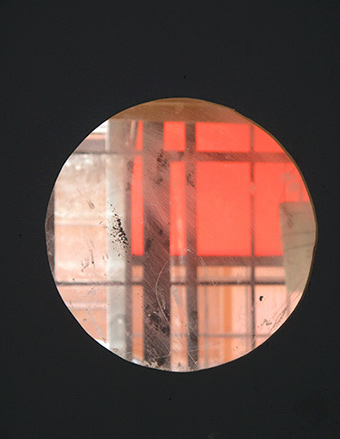

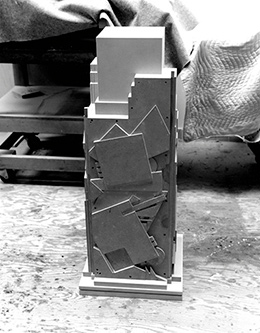

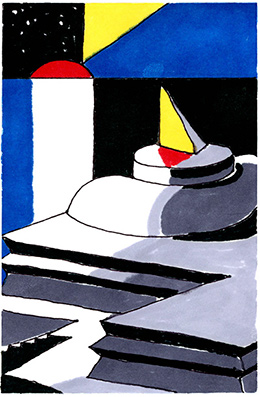

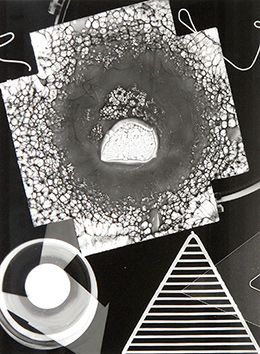

November 2010, ten years into the new millennium... Time to catch my breath... All summer long I was preoccupied with casting and finishing a bronze sculpture, nearly four feet high, which I call Homage to the Cube. It weighs over 220 pounds and requires two or three strong backs to move it. Despite its weight and scale it’s still a maquette or modello; that is a small-scale version of a much larger monument. The goal at the moment is to find the funding to enlarge it to perhaps 18 feet. Since its lines are hard-edged and geometric, rather than being cast in bronze, the giant version would be fabricated from sheets of corten steel, which rusts to a rich shade of red brown, while the cube itself would be fabricated from shiny sheets of stainless steel. In the end this means the sculpture follows a historical line that is really a progression of materials, all the way from paper to foam-core, from wood to bronze, and finally to steel. Perhaps that’s why I say sculptures, like people, live on a number of levels. “Live” because sculptures have a life if they manage to continually pique the imagination. What that means may change with time, fashion and exposure. On the other hand, some sculptors, like myself, go so far as to call our creations our children. Like all children the time comes when you have to let them go and find their way in the wider world. I know, because this October while I was in Berlin on a photo-shoot, my kid, ‘the Cube’, skipped town: going three thousand miles, from Berkeley, California to Miami; from the cement floors of Artworks Foundry glittering with bronze dust to considerably cleaner quarters in the Frost Museum on the campus of Florida International University. Returning to the foundry after a month away I discovered that I too could feel the pangs of the empty nest syndrome as my steel worktable looked so forlorn and empty. Bronze, before it tarnishes, has a moment when it seems on fire. I thought of the hours I spent hand sanding my kid, the Cube, to a mirror finish. The geometric relief had all the facets of a cut diamond set in gold, or was it in the end the simple, but ephemeral glow of youth? Sculptures share both a public persona and a private persona. For example, the public persona of a sculpture starts out with what you see, which is either the object itself, or a photograph enhanced perhaps by a description. In that case, Homage to the Cube is a four-sided column that is cut at the top in such a way that two corners are stepped and hold in place the contours of the cube that crowns the piece. The four sides of the columns are layered with complicated patterns of hard-edged reliefs. Each of the four sides is dominated by one of the four basic shapes of the geometric canon: the circle, the square, the triangle, and the cross. The latter refers to a cross or plus sign made up of four equally proportioned squares. This particular canon is drawn from the principles of Suprematism espoused just before the First World War by such disciples of Constructivism as Malevich and Tatlin in Russia, and subsequently in the Twenties disseminated at the Bauhaus in Germany by influential teachers such as Paul Klee and Moholy-Nagy. In Italy Futurists, such as Boccioni and Giacomo Balla digested all of these liberating innovations as they analyzed energy and translated speed into a hyper-kinetic yet visual vocabulary. What it really was: was a revolution of the eye. Cubism is and remains the most influential of all the many art and design movements that riddle and rock the twentieth century. It begins as a series of experiments by Picasso and Georges Braque in late 1908. Ultimately the movement can be traced to Cezanne’s passion for cylinders, spheres and cones whose determined volumes acted as a weighty correction to the insubstantial flicker of Impressionism. How does my sculpture fit into that historical scenario? It’s something of a bookend, because I created Homage to the Cube as a monumental as well as millennial celebration of the cube as the basic building block of human civilization. As mankind emerges from the cave, think of the cube as the cut stones or the baked bricks of the first houses: the cube being the catalyst that leads to ever more complicated temples, aqueducts, bridges, domes and coliseums. In the twentieth century think of the cube as shorn of decorative edifice as once again architects and designers heed the call for simplified forms and functional purity. Like many things that evolve, Homage to the Cube has a private persona, which can’t be seen except by the artist, who may or may not tell you of the making and the seeding. Since this is the history of a sculpture by the sculptor, clearly I intend to tell you, which requires a modicum of honesty. First of all, the Cube didn’t start out as a single column, but as two columns meant to support the entry arch of a large apartment building being built in San Francisco. The site was a street corner that now faces one of the convention auditoriums of Moscone Center. The year was 1988. The building’s developer was obliged by city law to spend some funds on artwork associated with the building’s design or decoration. The architect suggested I clad the two columns of the building’s formal entryway in a sheath of bronze decorated with patterns of relief. The entryway columns were narrow and wide rather than square. They were also stepped at the top: the highest step being 16 feet. I should point out, those steps still survive in the final version of the design. From the beginning I suggested to the architect I wanted to feature the four elements of the geometric canon of Suprematism. I worked on a quarter scale based on the projected height of 16 feet. The design quickly moved from the paper and pencil stage to the collage stage. I cut out scores of geometric shapes from black, scarlet and yellow paper, which were color keyed to the various depths of the relief. Each of the four broad sides of the columns were anchored by a large circle, square, triangle and cross, but the variety and number of dynamic shapes that surrounded them proved to be a challenging balancing act. Once those proportions were resolved I cut the shapes out of foam-core so I could see the precise relationship of the layers and contrasting depths. After that I had a carpenter build me two quarter-scale columns plus the archway pediment. I then taped the foam-core panels onto the columns and brought them to the architect’s office. After some months of indecision the developer finally told me he liked the idea but found it less troublesome to give money to the city’s arts fund in lieu of ornamenting his building. Of course, I was crestfallen, nevertheless I still felt so motivated by the project that I resolved to reconfigure the two columns as two legs of a sculptural side table, one whose backside would rest against a wall. I had my carpenter copy the foam-core panels in wood. We attached them to the columns with metal screws. The idea didn’t quite work. At that point my ‘Suprematist table’ took a rest and went into storage, At the same time I moved my working quarters from a tiny space in San Francisco to an enormous sweatshop across the bay in what proved to be a dangerous section of Oakland. Those cubist ideas, however, did not take a rest as I totally refocused my sculpture toward working in wood based on constructivist principles. I started a series of Temples and Towers, which were ostensibly shrines to honor my many friends who for one reason or another had died young. Then in a matter of seconds the Loma Prieta earthquake of October 1989 smashed all my new work. My new studio was only blocks from where the freeway decks collapsed. My floor was perhaps a microcosm, but like the road under the freeway decks, it was scattered with blocks and cubes. I decided to touch nothing until I had photographed the destruction. When I focused my lens on the haphazard patterns made by the falling blocks I thought of the poet Yeats and his famous refrain, “A terrible beauty is born”. Not only did the cube dominate my sculpture it now entered my photography and drawing as well. I soon reveled in the possibilities of the abstract, which could range from the agitated to the serene. Working late at night in an old photo lab with giant vats of chemicals I made a series of photograms that drew on the shapes of the colored papers that I had used in designing what was still ‘the Suprematist table’. Back in my studio in Oakland I went about rebuilding and revising the destroyed shrines. I also designed a suite of retablos, sculptural frameworks, which I envisioned as two-dimensional altars that could be hung from a wall. In 1995 after being shot at by some gun-toting teenagers I gave up my lease to the Oakland sweatshop and returned to casting bronzes at the foundry in Berkeley. All my new wood sculptures went into deep storage, however, ‘the Supematist table’ came back out. Inspired by my retablos I considered abandoning the table format in favor of four panels, which would be hung as bronze wall reliefs. It proved to be a long debate: are they too narrow? Will they be too heavy? Eventually I gave in to the magical power of numbers. The year was 1999 and I wanted to commemorate the change of millenniums with a design statement that was: both personal and public, both simple and complicated, both intellectual and spiritual. In the truest sense of the word it came together. In some ways it was simply a design problem. How do I combine four elements into one, but a singular and triumphant one that is more than just a sum of the parts? I did a lot of looking at the four panels and a lot of staring off into space. What may seem an obvious resolution now, was not obvious at the time. I did what I usually do: I stepped back and then returned to the problem totally cold and calm but with fresh eyes. Consequently, in the autumn of 1999, ten long years after I first started the design, its resolution finally came to me. No trumpets, just a nod of the head. That’s it! I’ll salute the cube since it’s at the heart of these endeavors! So I talked to my carpenter and we went about adapting the four wood panels to yet another re-configuration, this time a solitary one topped by a giant cube. A wood model, however, is just a step in the making of a monument. In 2000, at great cost and some investment of faith in the design, I had a blue silicon mold made of the wood model. Then my life took another unexpected turn as the attack on the twin towers of the World Trade Center in New York City on September 11, 2001 commanded the world’s attention as well as mine. I eventually spent more than a year on a personal journey with two cameras photographing America, its people, its cities and villages and the many memorials I discovered on my wanderings from sea to shining sea, that is from Cape Cod to the Santa Monica Pier. Memorials and memory are the business of sculptors, which is a sensibility that also informs my photography. I am not a one medium artist. Nevertheless, in 2003 I was once again back at the foundry where I suddenly felt compelled to start a new body of work called Trail Markers, which I refer to as geological cubism. Although the mold of the Cube remained in storage, the cube as an idea still possessed the center of my creative life. Suddenly it’s 2010. The Cube is now 22 years old. I’m 64 years old. With encouragement from architect and designer Sloan Schaffer in Miami, and the Frost Museum at FIU, I realize its legacy time, which leads me to pull the mold from storage. The owner of Artworks Foundry, Piero Mussi, sees that the mold is as finely calibrated as a Cartier brooch. He decides to make the wax of the Cube from a very refined green jewelry wax so the sculpture’s sharp edges will keep their crispness in the casting. Nevertheless, as artist’s do, I still made a few last minute design changes. I took off some tiny projectiles that distracted from the cube while I added another level to the very bottom of the base, slightly inset, which allows the piece to feel like it’s floating. During the summer of 2010, my kid, the Cube, finally got some respect as it finally marches through all the classical stages of lost wax casting: 1... making the wax from the mold, 2... erasing the seam lines from the wax, 3... attaching wax feed channels called sprues to the wax sculpture as well as inserting the core pins, 4... dipping the wax in the ceramic shell, 5... melting the wax from the shell, 6... pouring the molten bronze into the hollow shell, 7... breaking the shell off the bronze once it’s cooled, 8... cutting off the sprues and pulling out the core pins, 9... sandblasting away the remaining bits of shell, 10... welding together the various sections and welding shut the core pin holes, 11... grinding away any evidence of the sprues, 12... detailing or polishing the final metal surfaces until you have no idea how much effort went into this glorious piece of metal. I’m a hands-on type of sculptor at the foundry. Over the years I’ve cast over 85 different bronzes and of those I’ve often cast more than one. I’m hard-nosed about quality. I become personally and physically engaged with the metal, especially the very final surfaces. Frequently my hands are so soiled at night I can’t get the dirt out. I move from coarse sandpapers to fine sandpapers to delicate scrub pads. Applying the patina, that is adding the color with a torch and chemicals, is the last stage. However, the Cube proved to be so radiant in its final polish that I felt compelled to have it photographed for the record. After that I asked my patina master Karl Reichley to simulate what the Cube would look like in corten and stainless steel, which explains the rust browns of the sides and the silvery cube at the top. More photographs of course were then taken after the Cube was patinated, but I was already gone. I left for Berlin before the big wood crate was made. I never saw it loaded onto a cross-country truck bound for Miami. Like I said, with or without the sculptor, sculptures have a life. There is the making of a sculpture and there is the seeding. I often tell people, anyone who knows anything about art history can have fun with my work since it is full of cultural reference points ranging from the subtle to the obvious. I’ve actually had artists tell me they don’t go to museums because they don’t want to be influenced. I tell them, first we don’t live in a vacuum, and secondly, we all draw from experiences and exposure, either for inspirational models or content. My mind is a visual encyclopedia because I take the time to go to museums and galleries. I’ve also sought out collectors who have shared with me both their collections as well as the inevitable stories that come with being inveterate hunters and intrepid gatherers. Now it’s one thing to say I’ve been to many museum shows, but in the context of an essay focused on a particular work of art I think it is important to be specific and acknowledge those sources that introduced me to the world of the cube and Cubism. On an institutional level I am grateful to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and to the Museum of Modern Art in New York for the many exhibitions that were a constant source of enlightenment. I would particularly like to point out the Picasso Retrospective at MOMA in the summer of 1980 where I walked about in an absolute reverie, having this unique opportunity to see so many masterpieces of Analytic and Synthetic Cubism pulled together at one time. On a gallery level I am grateful to the informed exhibitions and extended friendships provided by Denis Gallion of Peacock Garden, and David Dutra of Twentieth Century Furnishings, both located in San Francisco during those heady days of the late Seventies and early Eighties when so many galleries and young collectors were passionate about Art Nouveau and Art Deco. Also in San Francisco, starting in 1980, Martin Muller of Modernism Gallery began an unprecedented series of exhibitions drawn from the Russian Avant-garde, 1910 – 1930, that provided me with first hand exposure to drawings and paintings by many of the great names of Suprematism and Constructivism such as Malevich, El Lissitzky and Ilya Chashnik. In New York I think of gallery directors such as Jonathan Hallam who shared with me his considerable knowledge of the Bauhaus introducing me to the pottery of Otto Lindig and the textiles of Gunta Stolzl. Of the many collectors I’ve known I am especially grateful to Tom and Adriana Williams in San Francisco who shared with me their passion for Symbolism and Art Nouveau. In Boston John Axelrod shared with me his passion for American design of the first half of the twentieth century, introducing me to such names as Kem Weber and Paul Frankl. In Michigan Jerome Shaw shared with me with his passion for American ceramics introducing me to the work of Wayland Gregory as well as the architecture of Eliel Saarinen and the sculpture of Carl Milles at the Cranbrook Academy, whose campus is regarded as a masterpiece of the Arts and Crafts Movement. If Homage to the Cube finds a permanent home at the Frost Museum, call it irony or natural inclination, but Miami like New York has been one of my second homes. The Cube owes more than a nod to the Art Deco architecture of South Beach. I started visiting Miami with some regularity in the mid 1980’s. What drew me there? No other than the master magician of Miami, Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. For a few years in the eighties and early nineties I had the privilege of now and then traveling in Mickey Wolfson’s charmed circle. What do you say when Mickey calls you from St. Louis and says get on a plane and meet him at the train station in San Antonio at 2 am. Two in the morning? Absolutely fortuitous, he says, because that leaves us two hours to see the Alamo under the full moon, and then at four we’re off to El Paso, and from there, we’ll cross the border and head for the Pre-Columbian ruins of Casas Grandes and after that Mexico’s Copper Canyon. It’s one of the great train rides of the world: scores of tunnels and breath-taking vistas. How can you say no? First of all, there is a staff of eight including a dessert chef. Then you are riding in two private railway cars hitched to the back of the train; the sleeping car is the very car used in Billy Wilder’s film Some Like It Hot, while the second and last car has an observation platform, where author and curmudgeon John Malcolm Brinnin, Mickey’s other guest, will either be sipping a very dry martini, or letting loose his lightning wit, full of casual quips about the young Truman Capote, the photographer Cartier-Bresson or the mercurial Welsh poet, Dylan Thomas. I once asked Mickey why he called me of all people that day. He said, well Zita, the last empress of Austro-Hungary, couldn’t make it, then he remembered that a topographical series of bronze discs I did called Metaphysical Landscapes made him think that I would really enjoy seeing Texas and Mexico. He was right. That trip also introduced me to the painted ceramics of the Mogollon culture of Casas Grandes, whose powerful geometry is certainly a corollary to my interest in the linear dynamics of Suprematism. Of course, today, circa 2010, Mickey Wolfson’s collections and fabled research library are housed in Miami Beach at the Wolfsonian, which I first saw as the Washington Storage Company building, then in need of much work. Now it is one of the architectural jewels of South Beach. I remember seeing Lincoln Road as a dilapidated street of empty shops. Mickey said, just watch, this is going to change and soon. Mickey is blessed with an infectious curiosity. Not only is travel an adventure, so is art and its variety of cultural messages. I happened to see the castle in Genoa when Mickey first bought it: Am I crazy or not crazy? I’ll let him answer that. Nevertheless I’ve dined with the late Maharani of Jaipur in Nervi and scooted around Portofino in the tiniest car with the Principessa X, who, again thanks to Mickey, took me to see the collection of paintings and sculpture in the home and gardens of Madama Jesi. She was then in her nineties, but she and her husband had been great patrons of the sculptor Marino Marini. Like Madama Jesi, who opened her home to me, Mickey is one of the great patrons of the proverbial you and me. By that, I mean everyone and anyone who cares to see his collection or make use of his great library whose focus is North American and European design history between 1885 and 1945. As a collector I used to spot the odd sculpture that might be appropriate for his collection. One requirement was that the price had to contain the number 7 somewhere, which made for interesting negotiations. I expect the most noteworthy find I made for Mickey is Benny Bufano’s monumental plaster of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt that was destined for San Francisco’s World’s Fair on Treasure Island in 1939, but for some reason was never used, yet somehow survived. Thanks now to the Wolfsonian’s climate-controlled storerooms it still survives, and more than just surviving it is available to students of design as well as the general public. Art is about communication. Art is about sharing. As an artist I share with you my vision. Museums, galleries, and collectors are repositories of many visions gathered together under one roof. All that adds up to access. Hopefully from that exposure you can be inspired to develop a vision of your own. If Homage to the Cube celebrates the Cube as a building block it is also a celebration of all those institutions and people like Mickey Wolfson or Patricia and Phillip Frost who are not content to merely entertain you, but who are truly ambitious, who mean to take a hungry eye and turn it into an educated eye. Now, if you don’t mind, I have to get back to work. I took 7070 photographs in one month in Berlin. I have to say the Cube was on my mind. I have a lot of editing to do. Stay tuned, as I have more to share with you, such as a suite of stones and shadows I may call Tempelhof, and a study of cubes compressed into compelling patterns, which I am already calling Denkmal. In Germany, and especially in Berlin, a Denkmal is a place to reflect. Yes, when I come to think of it, Homage to the Cube is a Denkmal. One vision feeds another. And when I’m gone that Cube will speak for me. Who knows what dialogues I have ahead of me? November 15, 2010 |

|

|||||||||

|

||||||||||

Tempelhof Suite

Tempelhof Suite